Some landscapes open wide and sweep your gaze to the horizon. Others turn inward, drawing you close, asking you to look carefully. Upper Antelope Canyon belongs to the latter. Tucked into the desert sandstone east of Page, Arizona, it is not a place of vast views but a narrow passage where stone and light come together in a moving performance.

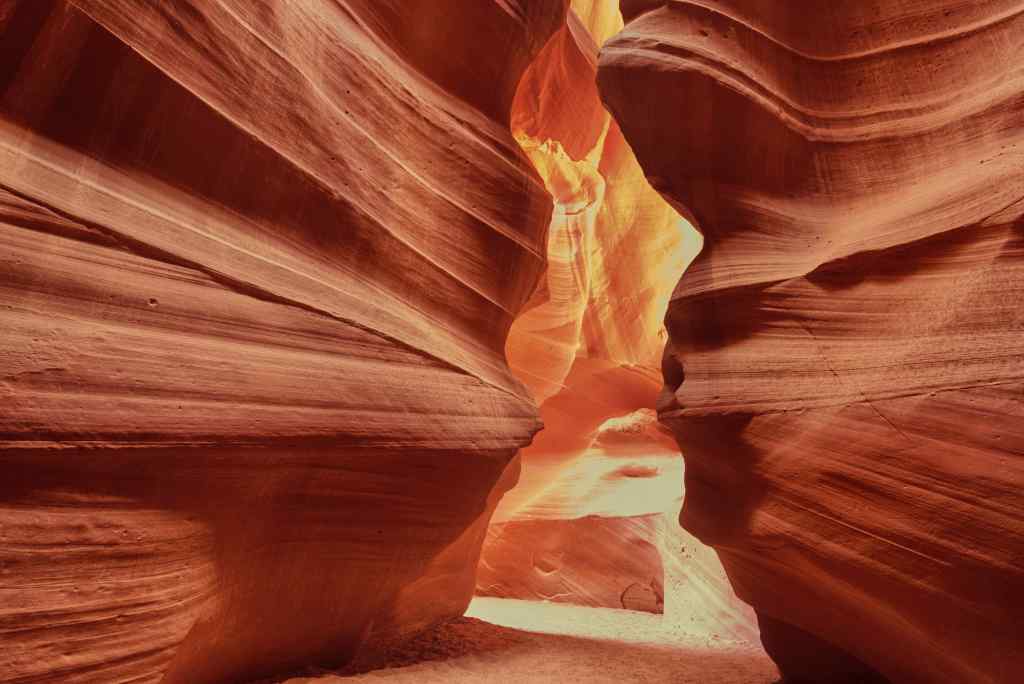

Those who enter discover not just geology but theatre. Sunlight filters down through cracks in the roof, spilling into the chamber below. The walls themselves glow with colour, shifting with every change in the sky. What looks dull and shadowed from outside becomes alive within. The canyon does not sit quietly; it shifts, breathes, and changes as the light moves.

Upper Antelope Canyon is known to the Navajo people as Tsé bighánílíní — “the place where water runs through rocks.” The name speaks to its origin. For centuries, flash floods coursed through these narrow cracks, carrying sand and debris that scoured the walls smooth.

Unlike many canyons that spread wide, this one is shaped like a narrow hallway. The bottom is broad and sandy, easy to walk upon, while the top narrows overhead into a slit of sky. The proportions create the canyon’s famous effect: shafts of light fall directly into the chamber, while the walls capture and reflect the glow. It is a design not of human hands but of time and water.

The most celebrated feature of Upper Antelope Canyon is its light beams. Around midday, especially in summer, shafts of sunlight angle through the cracks above and form columns of light that reach to the canyon floor. Dust or sand stirred into the air makes these beams visible, glowing as though the canyon were illuminated from within.

Photographers come from across the world to capture these fleeting moments. The beams last only minutes, shifting as the sun moves. Each one is slightly different — a straight column one day, a slanted ray the next. Guides often time tours to catch them, pointing out the exact spots where they appear.

Walking through Upper Antelope Canyon feels like stepping into a gallery where the exhibits are carved from sandstone. Floodwaters smoothed the walls into curves and ripples that look almost fluid. Some surfaces resemble waves frozen mid-motion; others curl like ribbons or fold like fabric.

These forms invite interpretation. Guides point out shapes in the rock — an eagle spreading wings, a woman’s profile, a bear at rest. Visitors see their own patterns, reading images into the stone as though it were a natural canvas. The canyon does not dictate what to see; it suggests.

The walls are also textured with fine horizontal striations, evidence of the sandstone’s layered formation millions of years ago. What flash floods shaped into sculpture was once ancient desert dune.

More than shape, it is colour that defines the canyon’s character. In the right light, the walls appear to glow from within. Reds deepen into copper. Oranges brighten to fire. Purples bloom in shadow. The effect is not painted onto the stone but created by reflection — sunlight bouncing down, scattering across the narrow walls, and amplifying colour.

At different times of day, the canyon looks like a different place. Morning brings soft illumination; midday delivers the famous beams and the brightest tones; late afternoon fills the passages with warmth and shadow. Cloudy days mute the spectrum, revealing subtler blues and greys. No two visits are alike, for the light is always shifting.

Inside the canyon, sound is softened. The narrow walls absorb and dampen footsteps, creating a hush that contrasts with the desert outside. Voices carry, but quietly, as though the space itself calls for restraint.

This silence, combined with the dim light, gives the canyon a quality many describe as spiritual. It is easy to understand why the Navajo regard it as a sacred space, a place shaped by powerful natural forces that command respect.

Though most visitors encounter the canyon as a dry corridor, water remains its author. Flash floods still sweep through on occasion, reshaping the floor, smoothing walls further, and carving new grooves. Rain that falls miles away can funnel into the slot, rushing through with sudden force.

These floods are dangerous, which is why access to Upper Antelope Canyon is only possible with a guide. Navajo guides know the signs, the risks, and the history of these waters. Their presence ensures not only safety but also continuity of knowledge. To walk through the canyon with them is to walk with those who understand both its beauty and its power. Their words turn the canyon into more than a corridor of stone — they make it a space layered with story, history, and reverence.

Upper Antelope Canyon has become an icon in the world of photography, a place where light and stone seem to compose images on their own. The famous sunbeams, the glowing walls, the rippling forms — all appear designed for the lens. Yet the canyon is not as easy to capture as it first seems. Light shifts quickly, colours change with the hour, and the narrow passage allows only a moment before everything is different again.

To photograph the canyon is to chase the fleeting. A sunbeam lasts only minutes before sliding away, a wall glows brightly then fades to shadow, and every step reveals an angle that will never look the same twice. It is this transience that makes the canyon so captivating: no picture is final, no visit repeats another. Each image, whether taken by a camera or simply remembered in the mind, is unique to its moment in time.

Upper Antelope Canyon is a place where nature reveals its artistry in silence and stone. Step inside, and the desert outside falls away; what remains is a narrow corridor where light pours down from above and colours seem to glow from within the rock. It is a passage not of distance but of depth, an intimate space carved by water and shaped by time.

It is a canyon of intimacy rather than scale, of detail rather than distance. Carved by floods, sculpted by time, and illuminated by the sun, it is both fragile and powerful, both delicate and commanding. To walk its floor is to experience not just geology but art — nature’s own gallery, alive with colour and change.

Leave a comment