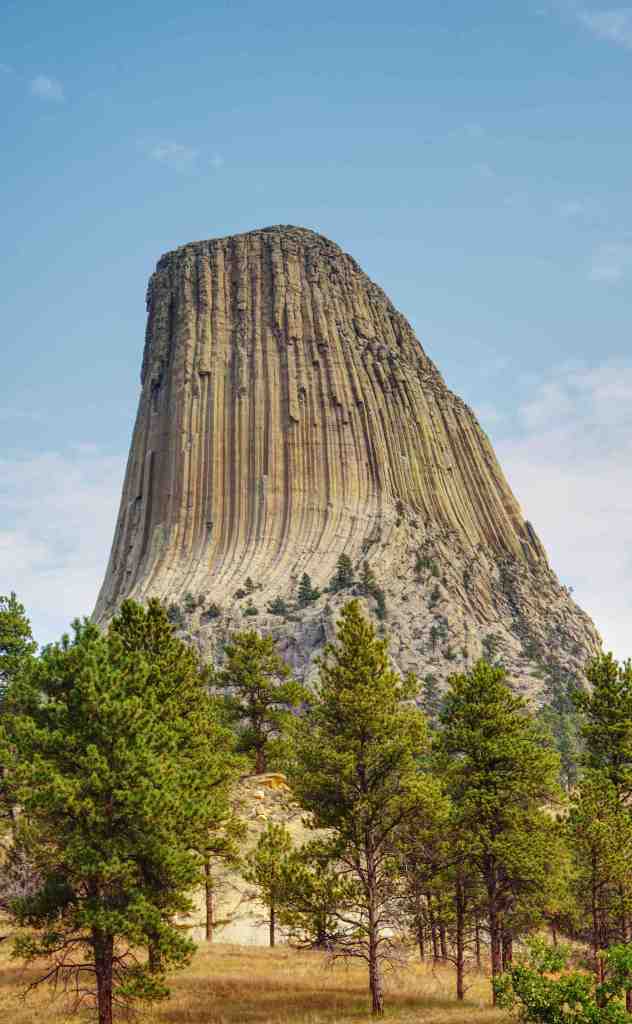

Some landmarks dominate not because they are the tallest or the widest, but because they rise where nothing else stands. Devil’s Tower is such a place — a solitary pillar of stone that thrusts upward from the rolling prairies of northeastern Wyoming. Its sheer columns catch the light at sunrise and glow red at sunset, a beacon visible for miles across the open land.

To stand before it is to encounter both wonder and weight. For the Lakota, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Arapaho, and other Indigenous nations, it is a sacred site, central to story and ceremony. For geologists, it is a riddle of volcanic forces and erosion. For travelers, it is unforgettable: a monument at once earthly and otherworldly, rooted in the prairie yet reaching for the sky.

Devil’s Tower rises abruptly from rolling prairie and pine forest, its sides furrowed with long vertical grooves. These grooves are columns of igneous rock, formed as molten magma cooled and contracted deep underground some 50 million years ago. Over time, softer surrounding rock eroded away, leaving the harder columns exposed as a massive, solitary butte.

The result is a form that feels both natural and otherworldly. The tower looks engineered, almost architectural, as if ancient hands had carved it into fluted walls. From certain angles it resembles an immense tree stump; from others, a fortress of stone. Its summit, flat and broad, stretches more than an acre, though only birds and climbers ever reach it.

Long before it was labeled “Devil’s Tower” on U.S. Army maps in the 19th century, the formation was known by many Indigenous names. The Lakota call it Mato Tipila, “Bear Lodge.” The Kiowa know it as Tsoaa-ee, “Tree Rock.” The Cheyenne refer to it as Noavo’ehe, “Bear’s Lodge Butte.” Each name reflects stories passed down through generations.

The modern name is the result of mistranslation. In 1875, during an expedition led by Colonel Richard Dodge, an interpreter rendered the original name as “Bad God’s Tower,” which was later shortened to “Devil’s Tower.” Despite its persistence on maps and in official designation, many continue to use the traditional Indigenous names, emphasizing the tower’s role as a sacred site rather than a devilish one.

The tower is woven into the oral traditions of many Plains tribes. A common thread in these stories tells of children pursued by a giant bear. Seeking refuge, they prayed for help, and the ground beneath them rose upward, carrying them into the sky. The bear clawed at the sides, leaving the deep grooves that mark the tower’s face. In some versions, the children were lifted so high they became stars — the Pleiades — shining still in the night sky.

Other stories tell of visions received at the tower, of ceremonies held nearby, of offerings tied to the trees around its base. For Indigenous communities, the tower is not simply a geological curiosity; it is a living place of connection between earth, sky, and spirit.

Recognizing this significance, Devil’s Tower was declared the first U.S. National Monument in 1906 by President Theodore Roosevelt. Yet the tower remains more than a monument. For many, it is a sacred site deserving reverence, where visitors are encouraged not only to observe but also to respect the traditions that surround it.

The most common way to experience Devil’s Tower is by walking the 1.3-mile Tower Trail that circles its base. From this path, the tower reveals itself from every angle. At times the columns loom vertical and sheer; at others, the grooves soften in the shifting light. Pines frame the view, and boulders — massive fallen fragments of the tower’s columns — line the slopes.

For some, Devil’s Tower is not only to be seen but to be climbed. Since the first recorded ascent in 1893, when two ranchers reached the summit using a wooden ladder still partly visible today, the tower has become a destination for climbers from around the world.

Climbing, however, is not without controversy. Out of respect for Indigenous traditions, the National Park Service requests that climbers voluntarily refrain from ascending during June, when ceremonies are most active. Many honor this request, balancing recreation with reverence. For those who do climb, the summit offers a rare view — prairie stretching to the horizon, the Black Hills in the distance, and the tower’s columns spread beneath their feet.

For the Plains tribes, the land surrounding Devil’s Tower is as sacred as the tower itself. Buffalo once roamed these grasslands in vast numbers, providing food, shelter, and spiritual connection. Even today, herds graze in nearby preserves, echoing the presence of an animal central to Indigenous life and ceremony. Just as the tower is bound to stories of bears and stars, the buffalo embodies resilience and sustenance, both woven into the cultural fabric of the region. Together, they anchor this landscape in memory, symbol, and survival.

Devil’s Tower is more than a striking formation on the Wyoming plains — it is a meeting place of earth and spirit. Its columns tell the story of deep geologic time, of magma cooling beneath the surface and stone standing firm as softer layers wore away. Yet around that same stone, generations have woven stories of bears, stars, and prayers, binding the tower to memory and meaning.

To walk in its shadow is to feel both histories at once. The tower is at once a natural landmark and a cultural sanctuary, a place where the forces of the earth meet the voices of tradition. Rising solitary against the horizon, it does not fade into the background of the prairie but commands attention, as it has for centuries. Devil’s Tower endures not just as rock, but as story — an emblem of endurance, reverence, and the quiet power of place.

Leave a comment