The rains return to Etosha like a promise, softening the dust and drawing green from the earth. Grass rises where there was none, stretching across the pan in fresh waves. Mopane trees shimmer with new leaves. And then—almost imperceptibly—a herd of antelope emerges from the grass. They move with a softness that feels rehearsed by the land itself, hooves barely breaking the stillness. At first glance they could be any impala, but then the light shifts, and their faces are revealed: a dark blaze running from crown to muzzle, a mark of difference that names them—the black-faced impala.

This is no ordinary antelope. This is one of Etosha’s quiet treasures, a subspecies found almost nowhere else on earth. Their presence is both a gift and a reminder: rare beauty is often fragile.

The black-faced impala lives as much by rhythm as by instinct. Mornings begin with movement—herds drifting out into the savanna to graze on fresh grass and browse on acacia leaves, their large eyes and swiveling ears ever-alert for danger. Midday brings heat, and with it, stillness. They seek the shade of mopane trees, chewing slowly, waiting for the long hours to soften into evening.

Their lives are structured around companionship and competition. Females and their fawns move together in nursery herds, a network of eyes and ears that offer protection. Young males linger at the edges, forming loose bachelor groups, learning the rules before the season of challenge arrives.

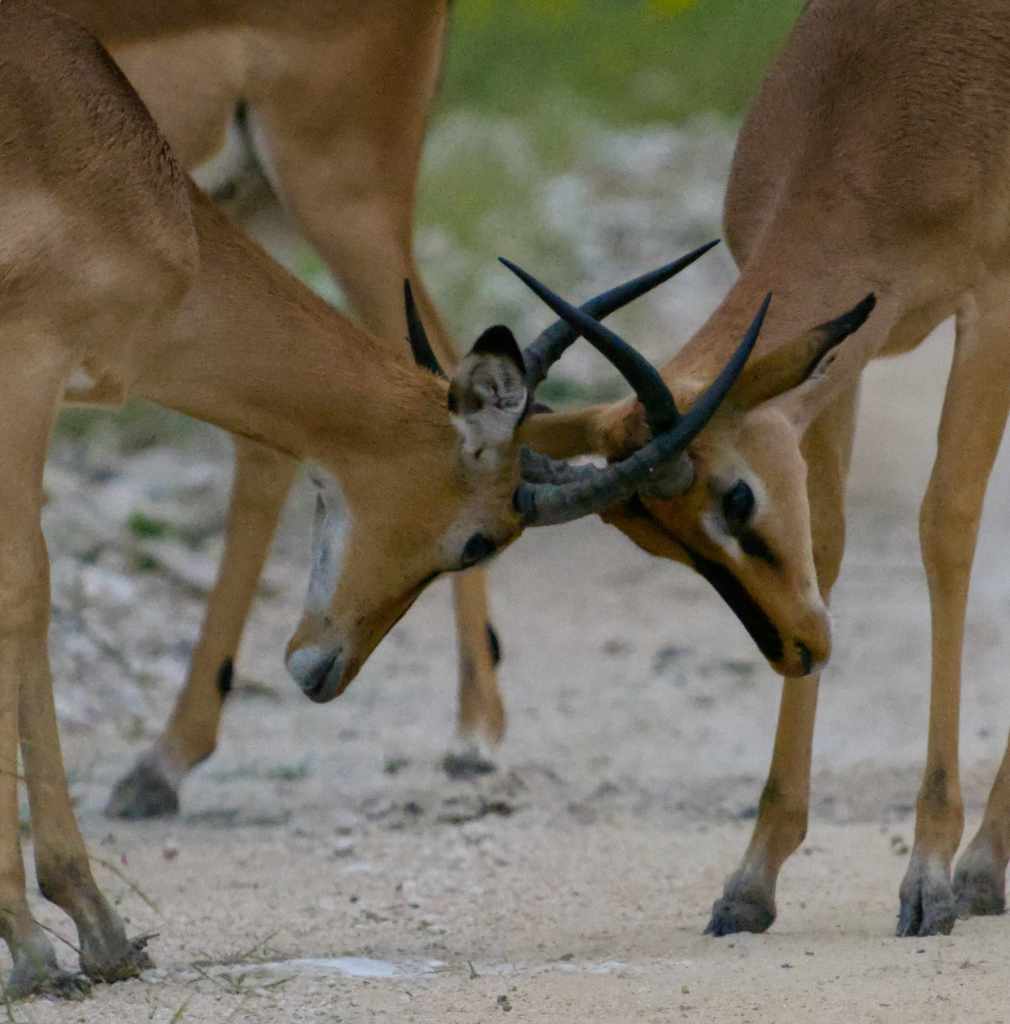

When the rut begins, the calm is broken. Males carve out temporary territories around water and grazing patches. Their calls, half-snorts and half-roars, carry across the plains. Horns clash, bodies collide, and for a brief season the herds are reordered by strength and stamina. Then the rains return, the grass grows, and new calves are born—delicate lives hidden away in tall grass until they can join the herd.

For all their elegance, black-faced impala are among the rarest antelopes in Africa. They exist only here in northern Namibia and a sliver of southern Angola, with Etosha holding the largest secure population. Rough counts suggest there are around 1,500 in the park itself, and only a few thousand in the world. Numbers are stronger now than in the dark decades of drought and hunting, but their range remains small, and their future never far from uncertain.

The greater threat comes from within: the possibility of blending into the far more numerous common impala. Where the two mix—on farms or in introduced herds—the subspecies loses its unique character. That’s why Etosha’s pure population matters so deeply. It is both a sanctuary and a stronghold, a place where the black-faced impala remains itself.

Through the long hours of the day, the black-faced impala moves like a shadow among the tall grasses, weaving through the sun-dappled plain with quiet grace. Calves dart nervously between the legs of their mothers, their small hooves barely making a sound on the soft earth, ears flicking at the slightest rustle of leaves or the distant cry of a bird. Older females graze with measured patience, selecting the tenderest shoots and balancing between nourishment and vigilance. Males patrol the edges of the herd, their lyre-shaped horns catching the light as they tilt their heads to scan for danger, reminding all who watch that strength and awareness are key to survival in these open plains.

During the rainy season, life for the black-faced impala is abundant and almost effortless. The grasses rise tall and lush, shading the calves and softening each step, while water is plentiful and food easy to find. Herds move freely across the plains, grazing and leaping through the greenery with a sense of ease that belies the harshness of the land. But when the rains cease and the dry season takes hold, the world changes. The grasses shrivel and brown, waterholes shrink, and the antelopes must stretch farther and move more carefully to find enough to eat. Yet through years of living in this rhythm, they have learned the art of endurance, surviving by patience, vigilance, and the quiet adaptability that has carried their herds across generations.

Etosha’s black-faced impala move across the plains with a quiet resilience, a living thread connecting the present to a past where these antelopes thrived in small, hidden pockets of Namibia and Angola. Their daily life—grazing, leaping through the grass, and watching the horizon with alert eyes—reminds us that rarity does not diminish vitality. Each herd is a small miracle, a glimpse of grace and survival in a landscape that demands both.

Yet their rarity carries a weight. With only a few thousand black-faced impala remaining in the wild, the future of the subspecies depends on careful stewardship. Protected populations in Etosha provide hope, but outside the park, pressures from habitat loss, drought, and hybridization with common impala loom. Their survival is a testament to conservation, to the careful balance of nature and human care, and to the enduring wildness of Etosha itself—a place where these extraordinary antelopes continue to move through the grasses, rare, remarkable, and unmistakably themselves.

Leave a comment